|

The first televised courtroom trial in the history of television happened in 1961, when a Jerusalem court tried Nazi SS Lieutenant Colonel Adolf Eichmann for crimes against the Jewish people. Eichmann was the head of Gestapo Department IV B4, and the mastermind behind deporting Jews into ghettoes and then into concentration camps. The direction of this self-proclaimed "Jewish Specialist" was largely responsible for the death of six million Jews. The world attentively watched their tubes, trying to anticipate what Eichmann would be like. We expected a monster, an infinitude of hatred, perhaps the devil incarnate. |

After observing the trial, philosopher Hannah Arendt argued in her controversial essay "The Banality of Evil" that Adolf Eichmann was just an ordinary guy. Eichmann is you and me. There was nothing strikingly evil about him. Eichmann's defense, like that of other Nazis, was that he was "just following orders." Furthermore, Eichmann said that he actually had no real ill will toward Jews. In any case, Arendt was ostracized by the Jewish community for the rest of her life, and Eichmann was hanged and cremated. His ashes were then peppered across the Mediterranean Sea.

The Milgram experiment may be the most famous experiment in psychology to date. It was conducted in 1963, shortly after Eichmann's trial. The world still needed an explanation for Nazi behavior. How could this have happened? Were these Nazis a different kind of human, with no thresholds of violence? Milgram showed that this was not so. Take the average American, put him in the right environment, and he will transform into a slaughterous Nazi.

Stanley Milgram 1963 > Milgram puts out a newspaper advertisement offering male Americans around the vicinity of Yale University to participate in a psychology experiment about memory and learning. Upon arriving at Yale, the participant is introduced to a tall, sharp and stern looking experimenter (Milgram) wearing a white lab coat. The participant is also introduced to a friendly co-participant, who is actually a confederate (a person pretending to be a participant, like a rigged audience for a magician). Milgram explains that the experiment investigates punishment in learning, and that one will be the "teacher", and one will be the "learner." Rigged lots are drawn to determine roles, and it is decided that the true participant will be the "teacher."

|

The confederate is strapped to a chair, and his arm is dotted with electrodes. Milgram instructs the teacher to read out word pairs from a list, such as "clear" goes with "air", or "dictionary" goes with "red". Afterwards, when the teacher says a word, the learner must regurgitate the other word that goes with the teacher's word. If the learner recalls the correct word, we move to the next word pair. Otherwise, he is given a voltage shock. These shocks increase in amplitude as more mistakes are made. However, Milgram says that "no permanent tissue damage will occur" (gee how reassuring). Shocks start at 15 volts, and grow in 15 volt increments.

|

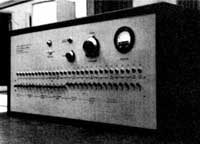

The shock generator is rather amusing. It has 30 switches, each labeled with a voltage ranging from 15 through 450 volts, and a verbal rating, ranging from "slight shock" to "danger: severe shock". The final two switches are labeled "XXX". |

The confederate responds in the following manner to the shocks:

| voltage | confederate response |

| 75 | grunts |

| 120 | shouts in pain |

| 150 | says that he refuses to continue with this experiment |

| 200 | blood-curdling screams |

| 300 | refuses to answer, mumbles something about a heart condition |

| +330 | silence |

As the participant perceives the confederate's pain, his conscience kicks in, and he begins to object to continuing the experiment. Milgram responds to these objections in the following way:

| objection | Milgram's response |

| first | "He's fine. go on." |

| second | "The experiment requires you to go on." |

| third | "It is absolutely essential to go on." |

| fourth | "You have no choice. You must go on." |

Question: What percentage of participants would deliver the full 450 volts?

Milgram asked his colleagues this question, and they responded with very small estimates. Maybe about 4 percent. Milgram himself didn't believe anyone would go so far.

Experimental Results

|

Milgram's results were alarming. Of the 40 participants he surveyed, 68% of them ended up delivering the full 450 volt treatment. 15 of the 40 ended up convulsing with epileptic laughter. Participants went temporarily mad and started tearing their hair out. Most amusingly, Milgram actually believed that the aforementioned experimental setup was the CONTROL case! He did not anticipate that subjects would conform at all in these conditions. |

| Right: Maximum shock voltage delivered by each of the 40 participants. Mode is XXX. Below: Shows how participant compliance slowly decays as voltages increase. 68% complied till the end! |

|

|

|

Milgram's quintessential psychology experiment trembled the world. It has been reproduced in many different countries, and is studied in most psychology courses, including two mandatory psychology courses at the US Military Academy. Unfortunately, not much has changed since 1963 in terms of unsound obedience; thousands are killed everyday by automatons who operate under the pretense of simply following orders.

An issue raised shortly after Milgram's explosion of fame was whether it was ethical to conduct such deceptive and distressing psychology experiments. Although most of the participants in Milgram's original experiment were very pleased to have participated in such an unforgettable learning experience, one of them was forever traumatized and had great difficulty continuing with his life. Regulations have now been introduced to prevent such psychological casualties; most notably, the requirement of informed consent, which demands that subjects be told what they will be doing before they actually do it. Whether Milgram's experiment was ethically justified is still the subject of heated debate today. On one hand, it seems inherently unethical. The world certainly learned a lot from it though. However, do the ends justify the means?