Karl J Sherlock

Associate Professor, English

Email: karl.sherlock@gcccd.edu

Phone: 619-644-7871

"Conjunctions" conjoin--or, link together--compound elements; when coordinating conjunctions are used to link two or more independent clauses, they create compound sentences.

"Coordinating" compound elements with a conjunction means showing the relationship between or among them, and it indicates how the weight of importance should be distributed. Seven conjunctions accomplish this, easily remembered by the anagram F.A.N.B.O.Y.S.:

Both independent clauses have equal distribution of focus and importance; they are presented side-by-side without bias to one or the other. In the example, a patient both visits a therapist regularly and shows no signs of improving. No judgment or inference is made. Instead, both data are offered with equal importance: this, and also that.

Both independent clauses have equal distribution of importance, but in contrast to each other. Using "but" in the example above, a straightforward contrast is offered, again without any inference or underlying agenda. It's simply a factual contrast: this is what's happening, but also that is what's happening.

Both independent clauses have equal distribution of importance; they are two main ideas contrasted with each other in a strange or surprising way--a twist. In the example, a hidden bias is being stated, that the contrast isn't logical. Why, we ask, does he continue to visit his therapist if he still shows no improvement? His action is unexpected--even ironic: this, yet, in spite of it, that as well!

Each independent clause competes for greater important because each is an option or a proposition. In the example above, the two options are presented without any subtext implied. They are merely two realistic propositions. Readers may feel strongly that they're aren't so much propositions as they are a dilemma, but this is merely because we are used to hearing passive-aggressive arguments being made in this manner: we assume the statement is suggesting, if he doesn't visit a psychotherapist weekly then he won't show any improvement. At face value, however, the example offers a literal proposition only: either this scenario may be chosen, or that scenario may be chosen.

There is virtually no different between "nor" and "or." "Nor" is simply the negation of two (or more) options: neither this is an option, nor that.

With "for," distribution is not equal. One of the independent clauses expresses a condition, while the other draws attention to its underlying cause: this, because of that; that as the cause of this. In the example, more attention is brought to his pattern of grudgingly visiting his psychotherapist weekly because it's the reason for his spotty improvement. (In another interpretation, one could surmise that his psychotherapist is so bad that weekly visits are the reason he continues to show no improvement.)

With "so," distribution is not equal. One of the independent clauses expresses a condition or a premise, while the other draws attention to an effect or a result of it: : that, because of this; this leads to that. In the example, focus is placed on his grudging decision to visit the therapist weekly in response to the lack of improvement. (in another interpretation, it can be suggested that he grudgingly acquiesced to further visits with his psychotherapist simply because he's not showing any improvement otherwise.)

A semi-colon is a form of punctuation, not a part of speech. However, it can be used sparingly as a form of generic coordinating conjunction. When two independent clauses are significantly related to each other, coordinating can sometimes be left implied rather than stated directly. Used in this way, semi-colons create a rhetorical effect as well as a semantic one. For this reason, they should be used as sparingly as a you would a rhetorical question.

The example above could easily use a comma and the coordinating conjunction "but." However, the contrast is implicitly understood in the second independent clause, so a semi-colon is acceptable.

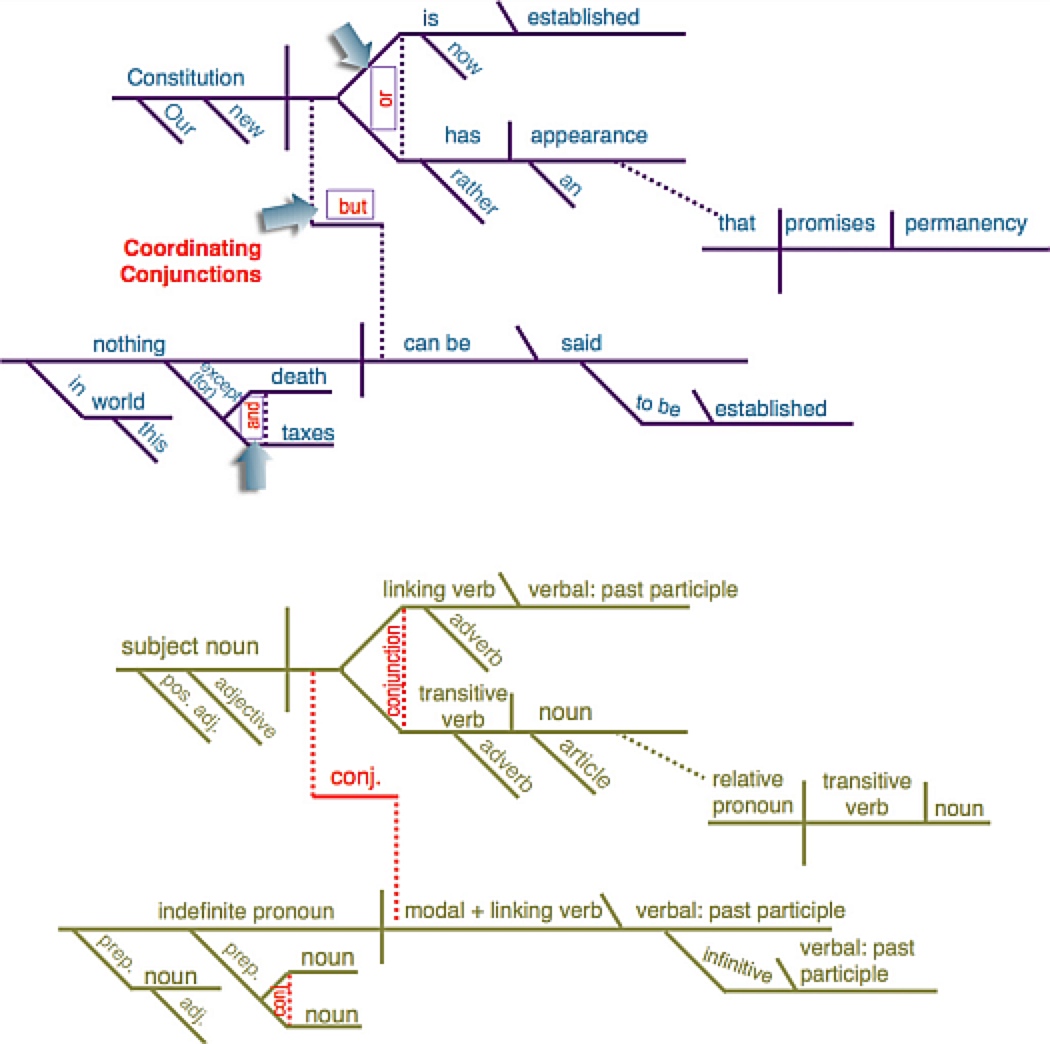

There are two ways to diagram coordinating conjunctions: as connectors between compound parts of speech and phrases; as connectors between clauses in compound sentences. Consider how and where in the following diagrams this quote from Benjamin Franklin uses coordinating conjunctions in both ways:

Karl J Sherlock

Associate Professor, English

Email: karl.sherlock@gcccd.edu

Phone: 619-644-7871

8800 Grossmont College Drive

El Cajon, California 92020

619-644-7000

Accessibility

Social Media Accounts