Karl J Sherlock

Associate Professor, English

Email: karl.sherlock@gcccd.edu

Phone: 619-644-7871

Take this pop quiz and find out how knowledgeable you are about modifiers.

1. The following, famously spoken by Neil Armstrong taking his first steps on the moon, contains a modifier error. True or false?

1. The following, famously spoken by Neil Armstrong taking his first steps on the moon, contains a modifier error. True or false?

2. Which interpretation of the following sentence is its likeliest intended meaning:

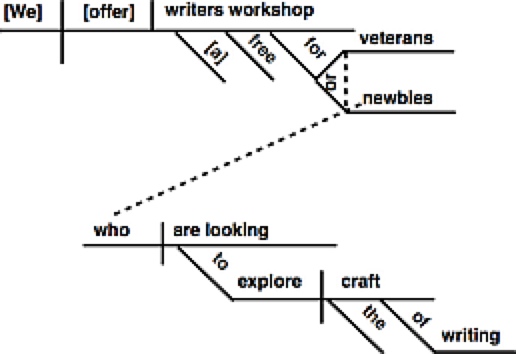

"Free writers workshop for newbies looking to explore the craft of writing and veterans, alike."

"Free writers workshop for newbies looking to explore the craft of writing and veterans, alike."

3. The following statement means that some dentists differ from others. True or false?

"All dentists are not alike."

"Without a syllabus and a textbook, it was difficult to keep up with the reading assignments."

"Without a syllabus and a textbook, it was difficult to keep up with the reading assignments."5. Whoever wrote the road sign at right...

Modifiers are words that describe and change your impression of something. That is, they modify the way other words are perceived or understood by adding more descriptive information. Modifiers include the following parts of speech:

Just as pronouns and possessive adjectives have antecedents to which they must clearly point "back", modifiers must also clearly point to one or more words as their subject. On a sentence diagram, if a word or phrase on a diagonal line cannot be placed under its subject, or if it's placed under the wrong subject, problems will occur in one of three major ways: as dangling modifiers, as misplaced modifiers, or as squinting modifiers.

Note: In this context, the term "subject" refers to the word(s) being modified, not the nominative "subject" of a clause. A subject is to a modifier what an antecedent is to a pronoun.

Just as the word "dangling" implies, a modifier with no apparent subject in its sentence is said not to hang on anything, and therefore dangle in the sentence. It hangs on nothing, the way the Cheshire Cat's smile lingers on the branch after the cat, himself, has disappeared. On a sentence diagram, a dangling modifier has nowhere to go. Although individual modifiers—adjectives and adverbs—can certainly dangle, more commonly they occur as dangling modifying phrases:

In each of the sentences above, the underlined phrase should modify a noun or verb in the main clause, but, really, no logical choice of subject can be found in the sentence. Like a pronoun reference error's vague antecedent, a dangling modifier's vague subject may actually be hiding in a previous sentence, but your readers didn't sign up for that much work. To fix it, you have to add the modifier's missing subject, sometimes requiring a little rewording of the entire sentence.

[*In this version of the sentence, "for example" is an apt replacement for "to give an example" because it does not require that anyone be responsible for giving the example; it is, instead, a more neutral expression.]

Unlike a dangling modifier, a modifier without a subject, a misplaced modifier confuses readers because it seems to modify the wrong subject. Sometimes it's done intentionally to create a humorously bawdy or clever effect, called a "double entendre” (“double meaning”):

In most cases, though, it just creates plain, ol' sloppy ambiguity, and the solution is simply to move the modifier closer to its subject. Take the following examples of misplaced modifiers:

Each of the underlined phrases in the sentences above should be moved to bring them closer to their subjects, or their subjects should be moved closer to them:

If you can train yourself to read (and hear) your own writing as your readers would, eventually you'll learn to avoid writing accidental misplaced modifiers and to compose devastatingly wicked double entendres.

Not knowing where the adverb “not” should go in a deductively reasoned statement is one of those examples of the banality of bad grammar. Advertisers seem especially careless about it, which creates the impression that the rest of us don't need to bother, either. (It's kinda like when the guys on TV news programs use words like “kinda” and “guys.”) Consider the following examples:

Each of these is an example of specious argument. In syllogistic reasoning, absolutes and qualifiers are used in order to set the parameters of a claim. Adjectives like “all,” “every,” and “any” are absolutes, while qualifiers such as “some” and “many” are not. You can imply qualifiers like "some" and "many" simply by saying something is not an absolute. And there's the crux of the mistake: in all three examples above, the word “not” has been paired with the verb instead of the absolute. Whoops! When corrected, the sentences should read as follows:

In many ways, misplacing the adverb “not” is the quintessential example of a misplaced modifier, as it aptly demonstrates in just a few words what happens on a larger scale with more complex misplaced modifying phrases and clauses. If you're prone to misplacing “not” in this way, it might take take a little practice before you can easily recognize the error. Such practice, however, is time well spent, because a logical mind is part of a beautiful mind, and if the mind of your sentence is illogical, your thoughts descend into madness. Beware!

The logic of “not” notwithstanding, nothing seems to make students furrow their brows as much as our discussions of "the squinting modifier." To the untrained eye, a squinting modifier seems like it should just be classified as a misplaced modifier. Sadly, no.

When a modifier is misplaced, it causes ambiguity, a lack of clarity. As discussed above, ultimately readers know how to fix the writer's mistake and change the location of the modifier to clear up the misunderstanding.

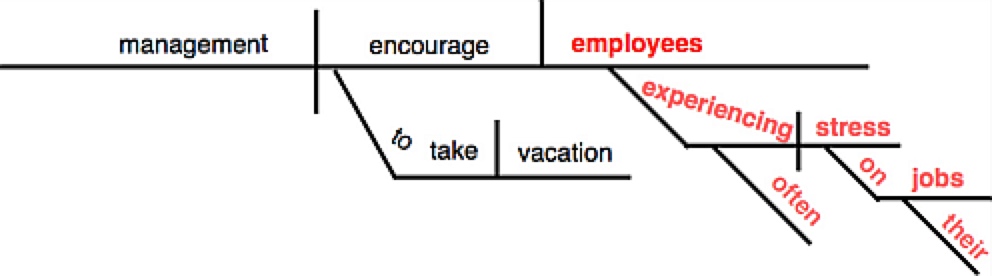

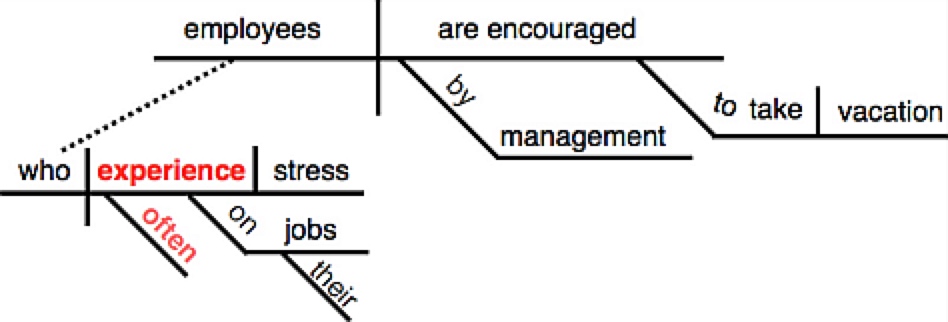

This example is clearly a misplaced participial phrase, because, if we just give it a little thought, we can suss out that the writer means the employees, not the management, are often experiencing stress on their jobs. If we were simply to reunite the participial phrase and the noun "employees," the sentence's meaning would become instantly unambiguous:

Management encourage employees often experiencing stress on their jobs to take vacation.

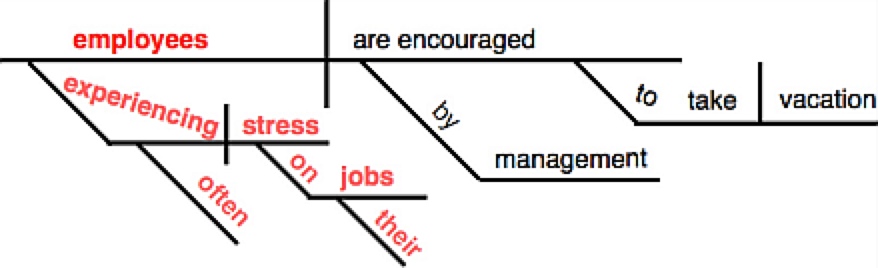

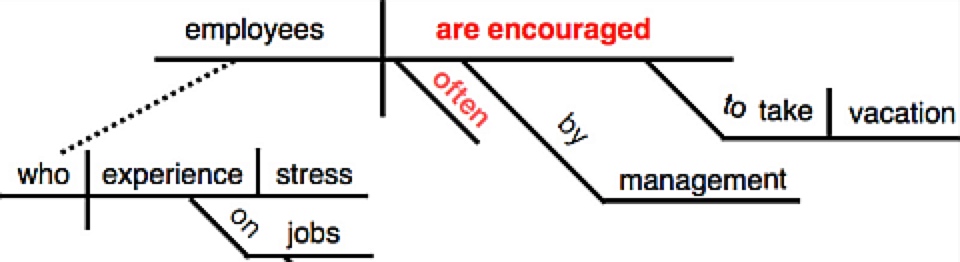

Alternatively, we could change "employees" to the role of subject, bringing the mountain to Allah instead of relocating the misplaced participial phrase:

Observe, though, that in both of the diagrams above the participial phrase "often experiencing stress on their jobs" is always connected to the noun "employees." A reader understands implicitly, it's the employees, not the management, who are stressed out. This is typical of a misplaced modifier, whose ambiguity is cleared up by solidifying that unclear relationship between the modifier and its subject.

A squinting modifier, on the other hand, doesn't cause ambiguity; it causes ambivalence, a lack of certainty. The reader is uncertain as to how to fix the writer's mistake, because the location of the modifier creates two choices, either of which is acceptable in meaning. A squinting modifier is, in essence, an adverb caught in a “sweet spot” of ambivalent meaning, capable of modifying a subject before it or a subject after it.

The word “often” lies in that one and only place that makes it grammatically entangled between two different clauses: it can mean either of the following:

In the first of these revisions, the word "often" is in the main clause and modifies the word "encourages"; in the next revision, the word "often" is in the relative clause and modifies the verb "experience." Here are a couple more brain-teasing examples.

[Does quickly adding sums lead to mistakes, or does adding sums lead quickly to mistakes?]

[Did the president make the announcement at the end of the day, or were workers laid off at the end of the day?] As with all misplaced modifiers, moving the squinting modifier closer to the word(s) it meant to modify helps to clear up the confusion.

Students whose understanding of grammar is clouded by years of bad experiences in English classes are always looking for ways to make grammar seem more relevant to other subjects. So, try this on for size: a squinting modifier is to sentence mechanics what the Heisenberg uncertainty principle is to quantum mechanics.

No, I'm not joking!

I've drawn this analogy between quantum and sentence mechanics because the system of forces we believe hold together the material universe are the very much like the forces used to hold together a thought. The uncertainty principle of quantum mechanics suggests there's something not quite right with the order of the universe—at least as we currently understand it. The squinting modifiers that upset your sentence mechanics suggest there's something not quite right with the mind of the sentence as you've written it. If you're confused by quantum mechanics or the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, you might understand, then, why squinting modifiers are confusing to readers, and why they run afoul of the rules of grammar

A common mistake in the use of modifiers is to confuse adjectives with adverbs. A lot of informal and idiomatic usage permits certain substitutions between adjectives and adverbs, but in formal and academic writing, this is strictly forbidden. The following are examples of frequently confused parts of speech.

ADJ |

ADV |

||

healthy |

healthily |

I eat healthily. |

I eat healthy food. |

nice |

nicely |

He seems nice. |

He dresses nicely. |

right |

correctly |

I live correctly. |

I make the right choices. |

fast |

quickly |

I move quickly. |

I drive a fast car. |

bad |

badly |

I feel bad. I feel unwell. |

She sings badly. |

terrible |

terribly |

It feels terrible. |

It hurts terribly. |

good |

well |

I did good.* I did well. |

I feel good. I feel well. |

*This means, "I made a positive impact," not "I performed well."

A good many prepositions look exactly like other words that serve as other parts of speech. Take, for example, the following sentence:

Out of all the uses of the word "like" in this sentence, only one is a preposition. Can you tell which? It's maddening, isn't it, because "like" can also be a verb, an adjective, an interjection, or a comparative subordinator (a kind of subordinating conjunction). This means, "like" when used in one part of speech is a different word from "like" used as another. Even though they may have related meanings, they're different words. Get used to that. In fact, you already are used to it, because you accept that words like "bass" and "bass" can mean completely different things: one is the opposite of "treble" and the other is a kind of fish. You accept that "bear" and "bear" mean different things: one is a verb meaning "carry" while the other is a big furry animal. You accept that the "Reading Railroad" of Monopoly has nothing to do with the Reading Rainbow of children's educational programming Resign yourself to the fact that the word "like" and other prepositions are homonyms. Evaluate them on their role as a part of speech, not on what they sound like.

The prepositional phrase in this sentence is "like lobster and mussels," because the preposition "like" points to an example; it's synonymous with "such as." The predicates "likes seafood" and "like pizza" both use "like" as a verb; "like foods" uses "like" as an adjective, meaning "similar" or "comparable"; "like Corey" and "like we" are comparative statements. As you've probably already guessed, "Dude, like..." is an interjection.

Misidentifying a conjunction, adjective, or verb as a preposition is one of the major confusions for students attempting to diagram sentences, which is why I advocate sentence diagramming: you have to sort out these differences and understand the grammar in order to complete the diagram.

The single most common error of preposition confusion occurs with the infinitive particle, "to," which students routinely mistake for the preposition "to." They ain't even related, so get used to it, as well as the many other prepositions that have homonym counterparts in other parts of speech:

Preposition: "Can we talk about the homework?"

Adverb: “On the grass, cups were scattered all about.”

Noun: “They did an about face”

Preposition: "My grades were above the average."

Prefix: above-mentioned; etc.

Preposition: "Is there really life after death?"

Conjunctive Adverb: “After, we went to dinner.”

Subordinator: “After we see the movie, let's go to Denny's.”

Prefix: aftermath; etc.

Preposition: "Aside from you, who else knows?"

Adverb: “Stand aside!”

Noun: as an aside

Preposition: "At the next opportunity, we're leaving."

Adverb: “Where are you at?”

Preposition: "Before the show, we had a few drinks."

Conjunctive Adverb: “Before, everything was better.”

Subordinator: “Before we make a mistake…”

Preposition: "I'm right behind you."

Adjective: “I'm behind in my homework.”

Adverb: “He's falling behind.”

Noun: "That guy's got a nice behind.”

Preposition: "That remark was below the belt."

Adverb:“Your exams all have below average scores”; “Let's go below with the other passengers.”

Preposition: "He keeps a suitcase beneath their bed ."

Adverb: “Go beneath now, for safety.”

Preposition:"Place the salad fork beside the dinner fork." confused with conjunctive adverb “besides”: "Besides, who would know?"

Preposition:"By land or by sea?" Suffix and Prefix:standby; bygone

Preposition: "I had shivers down my back."

Adjective: “She's feeling down today”; “The house is looking run-down.” Prefix: downtown; downturn

Noun: "They picnicked on the campus downs."

Preposition: "They all agreed, except for Lisa."

Subordinator: “It would have been great, except (that) no one came.”

Verbal (rare): “An ID is required by all, excepting infants.”

Preposition: "For love, I would do anything."

Coordinator: "He knew where to go, for he'd been here before.” (Confused with “fore.”)

Preposition: "In a month, you'll have forgotten about this."

Adjective: “They're sporting the in fashions.”

Subordinator: “I'm troubled by it, in that he's so much older than you.”

Noun: “He has an in with the hiring committee”; “the ins and outs of finance”

Preposition: "Inside the office, we're just co-workers."

Adjective: “He's guilty of inside trading.”

Adverb: “Come inside”; “Inside, it was warm.”

Noun: “The inside of the car is quite nice.”

Noun Adaptations: "Insider”; “insides”

Preposition: "We enjoy restaurants like this."

Adjective: “The two have like interests”

Comparative Subordinator: “I sound like he does.”

Interjection: “Like, you know, so what?!”

Verb: “I know what guys like.”

Prefix: “like-minded”

Preposition: "An asteroid will pass near Earth today."

Adjective: “It will be a near miss”; “You are near and dear to me.”

Adverb: “They're near finished” (i.e., “nearly”)

Preposition: "You are the man of my dreams."

Interjection: “I kind of, sort of love you, you know."

Colloquial solecism: “must of” “could of” (instead of “have”)

Preposition: "Off the beaten path, wilderness can be scary."

Adjective: “I'm having an off day”; “Yuck! This ham is off!”

Colloquial: “stand-off-ish”

Preposition: "I'll have egg salad on whole wheat toast."

Adjective: “She's always on”; “the on position”; “They're on to you”

Adverb: “Walk on, walk on with hope in your heart” *(onward); “I didn't mean to turn you on.”

Preposition: "Please leave out the side door instead."

Adjective: “I'm out to my family.”

Adverb: “Shake it out” (outward); “She turned it out.”

Noun: “We're on the outs.”

Prefix: “out-source”; “outtake”; etc.

Preposition: "Outside city limits, we drive faster."

Adjective: "She presents an outside opinion.”

Adverb: “They held the class outside.”

Conjunctive Adverb: “Outside, the sky was gloomy.”

Noun: “The outside was painted beige”; “The apple's outsides looked bruised.”

Noun adaptation: “outsider(s)”

Preposition: "The cow jumped over the Moon."

Adjective: “I'm over this guy.”

Adverb: “I'll hand the mic over to you.”

Prefix: “overcoat”; “over-achiever”; “overlord”

Compound Noun: take-over; etc.

Colloquial: “over and out”

Preposition: "We walked right past him."

Adjective: “Past events weren't this bad.”

Post-Positive: “In ages past, kings did rule the land.”

Prefix: “past-time”

Preposition: "Since ancient times, humans have befriended parrots."

Adverb: “I've loved you ever since.”

Subordinator: “Since we never go out anymore, I'm joining a club.”

Preposition: "Love endures through all trials."

Adverb: “Are you pushing through?”

Prefix: “through-way”

Preposition: "To turtles, a shell is a home."

Infinitive Particle: “To be, or not to be.”; “To Live and Die In L.A.” (Often confused with “too”)

Preposition: "Under the boardwalk is where I'll be."

Adverb: “Let's dive under and explore the reef.”

Prefix: under-bite; underwear; etc.

Preposition: "The gun is underneath the mattress."

Adverb: “Underneath lay a folded dollar bill.”

Preposition: "She worked right until the deadline."

Subordinator: “I'll love you until the cows come home”

Preposition: "I parked the car up the street."

Adjective: “Tracy always looks on the up side of life.”

Adverb: “Up we go, into the wild blue yonder.”

Prefix: upstanding; upended; upstart; etc.

Noun: “I know all about life's ups and downs.”

Preposition: "Take us with you."

Prefix: withstand; withal;

Preposition: "That's the story in a nutshell."

Adverb: "The truth lies within.”

Preposition: "He left without his wallet."

Adverb: “Without, the freezing weather awaits us.” “I'll go without this time.”

1. The following, famously spoken by Neil Armstrong taking his first steps on the moon, contains a modifier error. True or false?

ANSWER: True. This statement was supposed to be, "One small step for a man; one giant leap for mankind." The missing indefinite article ("a") makes the statement contradictory, because, without it, "for man" and "for mankind" mean exactly the same thing: "for humankind." A step for humankind cannot be, both, small and gigantic.

2. Which interpretation of the following sentence is its likeliest intended meaning:

a. an inexperienced writers' writing workshop whose organizers are looking to explore the craft of, both, writing and veterans

b. a workshop, free of charge, for new writers or experienced writers alike, who are looking to explore the craft of writing

c. workshop for not-for-pay writers who are new to writing and who are looking to explore the writing craft as well as explore issues of interest to veterans

d. rescued P.O.W.s conduct a workshop on behalf of new writers, all in hopes of exploring how to write about being ex-military

e. all of the above

f. none of the above

ANSWER: B Technically speaking, all the answers are possible, even if some leap to creative connotations with words like "free" and "veterans." The most likely meaning, however, is to be found in B, despite the confusing placement of the word "veterans" in the long modifying prepositional phrase with its compound object. The best ways to correct the sentence to resolve this confusion are as follows:

Free writers workshop for veterans or newbies who are looking to explore the craft of writing.

Free writers workshop for veterans or newbies who are looking to explore the craft of writing.3. The following statement means that some dentists differ from others. True or false?

ANSWER: False. The statement should read, "Not all dentists are alike" or "Dentists are not all alike." Why? Because "some" and "all" are contradictory ideas, while "some" and "not all" are not).

4. What, if anything, is wrong with the following statement? (Select all that apply.)

a. Nothing. The sentence is well written, as is.

b. It has a modifying phrase that should be moved to a better place in the sentence.

c. It has a modifying phrase that doesn't clearly modify anything in the sentence.

d. It has a pronoun reference error, due to vagueness.

e. It has a pronoun reference error, due to ambiguity.

ANSWER: D. It contains, both, a vague pronoun reference ("it") and a dangling modifier ("Without a syllabus and a textbook"). The sentence must state who is without a syllabus and textbook: "Without a syllabus and a textbook, I found it difficult to keep up with the reading assignments" or "Because I was without a syllabus and a textbook, it was difficult to keep up with the reading assignments.”)

5. Whoever wrote the road sign at right has…

a. written it perfectly as is.

b. accidentally omitted the word "Please".

c. misplaced the modifying word "Airport".

d. neglected to use the preposition "For."

ANSWER: D. The sign is missing a preposition, "For Cruise Ships, use airport exit." Sign writers are traditionally forced to use minimalism in signage: the fewest words to convey the most information in one glance, so this sign writer does not deserve our insults. However, a simple preposition in this case would have made sure the object of the preposition ("cruise ships") is not confused with the subject of the imperative sentence ("you").

Karl J Sherlock

Associate Professor, English

Email: karl.sherlock@gcccd.edu

Phone: 619-644-7871