Karl J Sherlock

Associate Professor, English

Email: karl.sherlock@gcccd.edu

Phone: 619-644-7871

The term "linking verb" is a twentieth century term for what used to be called the "copulative verb." Perhaps in the interest of protecting youngsters from the immodest discussion of copulation, educators and grammarians moved over to a term with fewer sexual overtones (unless, of course, chains have a place in one's romantic routines). Truthfully, "copulative" says it better and more accurately. To "copulate" simply means, "to couple," as in a power coupling (not the "Napoleon-and-Josephine" variety). In grammar, a copulative verb couples, or links, the subject with a complement. It renames or identifies the subject with a specific thing or characteristic.

If these questions sound like you're in a philosophy class instead of an English class, that's no accident. Linking verbs express who and what things are, and what they're perceived to be. Linking verbs are existential, ontological, and phenomenological. No matter. The variety of these questions should be a hint as to the many different ways that subjects can be complemented or identified, and this will be taken up in more detail further down the page. Before we go there, however, let's first take up the matter of complements in more detail.

In Plato's Symposium, Aristophanes offered his now famous explanation of the origins of love and coupling: before the time of human history, the gods had fashioned people more like conjoined twins connected at the back. To punish them for trying to overthrow Olympus, Zeus cleaved them in two, leaving them with an eternal longing for their "other half." This search for wholeness became the explanation for the origins of love and coupling—copulation. (Even now, sex is sometimes humorously referred to as the "beast with two backs.") Love, in other words, was the quest for one's complementary self. So it goes with the copulative verb, which assumes that the subject is made whole by being joined with its complement.

“Complement” should not be confused with its homonym “compliment.” To complement means two or more things, ideas, or people belong together. When you ask the restaurant server to recommend a wine, she recommends what will complement the meal you’ve selected; when you buy a tie or a scarf, you think about how these will complement a jacket you own. In each case, you hope to be able to give or receive compliments for your choice, but that's a different matter.

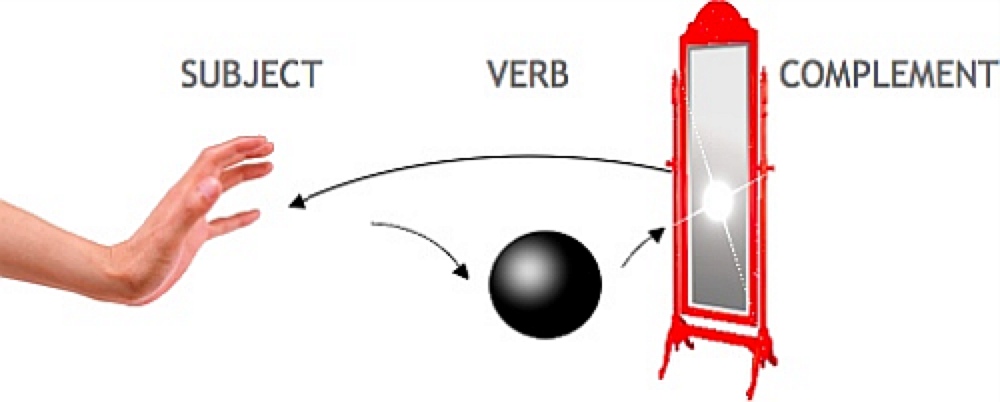

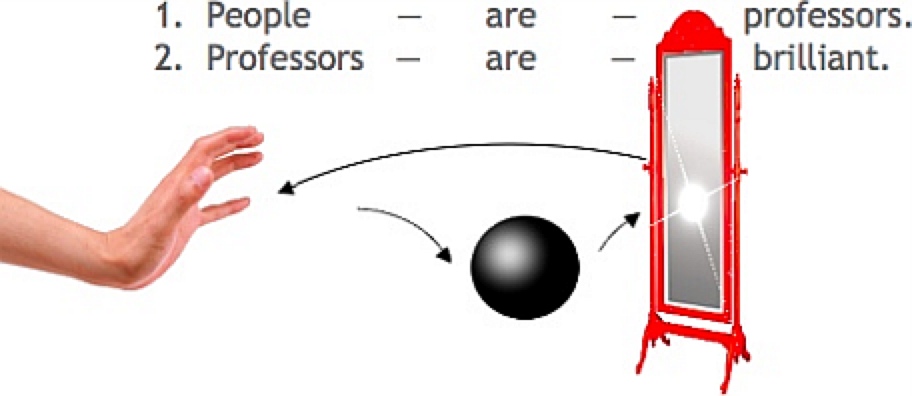

Linking verbs take two kinds of complements: noun complements or adjective complements. (Other parts of speech that act like these, such as pronouns or participial phrases, also work as complements.)

Parts of speech that can be noun complements include:

Noun complements are sometimes called the "predicate nominative" because the "Subject" case is also known as the "Nominative" case, and a complementary noun can be switched with the subject. In fact, the complement noun is always written in the subject case. This is extremely important for pronouns that are used as complements; the most frequent pronoun case error occurs when writers use the object case of a pronoun, instead of its subject case, after a linking verb. (See “Pronoun Errors” for more info.)

Any word, phrase, or clause that can modify a noun (or a part of speech that acts like one) can be an adjective complement. These include:

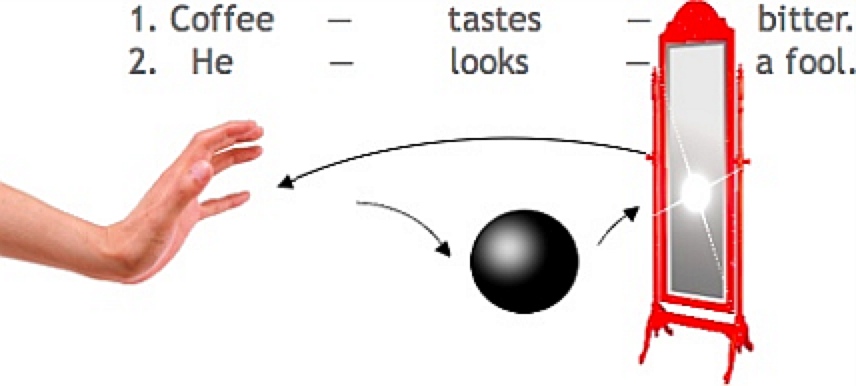

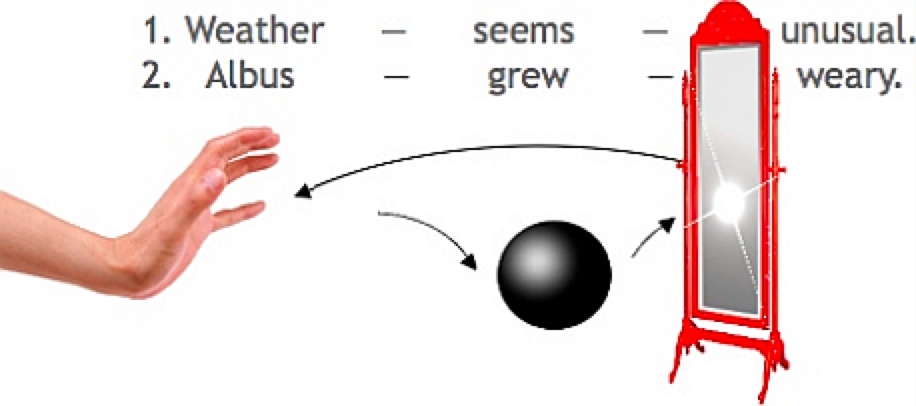

In all of these, the complement reflects some quality or status back onto the subject. For this reason, we think of a linking verb bouncing back to the subject, instead of forward to an object.

Linking verbs take the following forms:

Noun complement:

Adjective complement:

Noun complement

Adjective complement

[Note: Noun complements after sensory linking verbs are less common than adjective complements and are often associated with the Subjunctive Mood. Furthermore, one should be careful not to confuse the transitive versions of these verbs with the linking verb versions. Transitive verbs are used actively and take objects: "He smells the cheese." Linking verbs are used to indicate a sensory impression: "He smells" or "He smells like cheese."]

[Note: As with sensory linking verbs, several of these linking verbs can also be transitive verbs that actively take objects, or intransitive verbs: "Beverly grows orchids"; "He remained at home"; "Casey proved his point."]

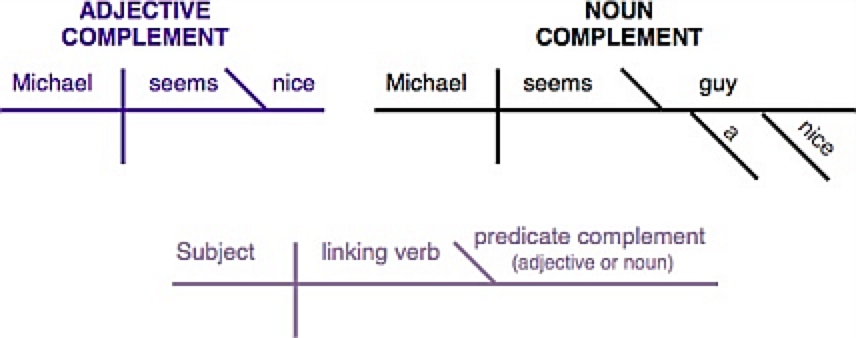

Diagramming a clause with a linking verb is similar to diagramming transitive and intransitive verbs. The only difference is that there's no object. Instead, there's a complement that renames or describes the subject. To indicate this, instead of a vertical line to separate verb from object, a diagonal line is used to slant the complement back in the direction of the subject:

| ADJECTIVE COMPLEMENT | NOUN COMPLEMENT |

| Michael seems nice. | Michael seems a nice guy. |

Instructor: Karl Sherlock

Grossmont College • 8800 Grossmont College Drive • El Cajon, CA 92020 • 619-644-7000

The Mind of a Sentence: A Guide To Parts Of Speech

Diagramming and Selected Topics, With Illustrations and Exercises

2nd edition. © 2014 Karl J. Sherlock

This website and its contents are intended as educational materials in a remedial skills course and may not be used for profit. Reproducing, redistributing, or reposted the content of this site, whether whole or in part, is forbidden without the express permission of the author. Please direct inquiries and comments to karl.sherlock@gcccd.edu.

Karl J Sherlock

Associate Professor, English

Email: karl.sherlock@gcccd.edu

Phone: 619-644-7871