Karl J Sherlock

Associate Professor, English

Email: karl.sherlock@gcccd.edu

Phone: 619-644-7871

"Degree" refers to the way adjectives can incrementally increase or decrease in intensity. Just as verbs conjugate by time in the past, present, and future, adjectives that can be conjugated in degrees in the positive, comparative, or superlative form. The positive degree is the base form of the adjective; the comparative degree is used for comparisons between two, phrased with "than," "as," "as…as" or "like"; and the superlative degree assumes a "winner" in a contests among three or more nouns.

"Degree" refers to the way adjectives can incrementally increase or decrease in intensity. Just as verbs conjugate by time in the past, present, and future, adjectives that can be conjugated in degrees in the positive, comparative, or superlative form. The positive degree is the base form of the adjective; the comparative degree is used for comparisons between two, phrased with "than," "as," "as…as" or "like"; and the superlative degree assumes a "winner" in a contests among three or more nouns.

Of course, not all adjectives can be measured in degrees. Some of the indefinite adjectives are like this. For example,

However, adjectives that can change into comparative and superlative forms in most cases will take either "-er" and "-est or "more" and "most" depending on the number of syllables in the base (i.e., positive) form of the adjective. (Also depending on the base adjective's original spelling, certain alterations to the spelling may also be needed with the addition of -er or -est.)

Short adjectives of one or two syllables express degree by adding -er and -est.

nice |

nicer |

nicest |

dull |

duller |

dullest |

little |

littler |

littlest |

true |

truer |

truest |

dry |

dryer |

driest |

Some adjectives of two syllables always use "more" or "most"; among these are adjectives that end in -ous when they're in their positive form:

algous |

more algous |

most algous |

awesome |

more awesome |

most awesome |

callous |

more callous |

most callous |

famous |

more famous |

most famous |

porous |

more porous |

most porous |

cavernous |

more cavernous |

most cavernous |

perilous |

more perilous |

most perilous |

ravenous |

more ravenous |

most ravenous |

With some adjectives you have the luxury of choosing either "-er/est" or "more/most":

sure |

surer (more sure) |

surest (most sure) |

real |

realer (more real) |

realest (most real) |

austere |

austerer (more austere) |

austerest (most austere) |

clever |

cleverer (more clever) |

cleverest (most clever) |

common |

commoner (more common) |

commonest (most common) |

mellow |

mellower (more mellow) |

mellowest (most mellow) |

severe |

severer (more severe) |

severest (most severe) |

The rest, three syllables or more, use "more" and "most" to express comparative and superlative degrees.

simplified |

more simplified |

most simplified |

interesting |

more interesting |

most interesting |

satisfactory |

more satisfactory |

most satisfactory |

good |

better |

best |

bad |

worse |

worst |

far |

farther |

farthest |

little |

less |

least |

much |

more |

most |

Some weirdly express the superlative in a post-positive form. (See "Post-Positive Adjectives.") Most of these, however, have positive degrees that are obsolete or less common, having evolved in our language to become prepositions:

fore (in front of) |

former |

foremost |

neath (under) |

nether |

nethermost |

hind (behind) |

hinder |

hindmost |

up |

upper |

uppermost |

top |

topmost |

The comparative and superlative degrees can also be expressed negatively using "less"

and "least." However, there is no option, then, to use "-er" or "-est"; you must use only

"less" or "least":

sure |

less sure |

least sure |

happy |

less happy |

least happy |

successful |

less successful |

least successful |

monotonous |

less monotonous |

least monotonous |

incorrigible |

less incorrigible |

least incorrigible |

The comparative degree can be expressed in more subtle increments.

When there is already a precedent for a comparison, you may use the adverb "even" before the comparative form of an adjective, to suggest an intermediary degree short of superlative:

qualified |

more qualified |

even more qualified |

most qualified |

wealthy |

wealthier |

even wealthier |

wealthiest |

prepared |

less prepared |

even less prepared |

least prepared |

clear |

less clear |

even less clear |

least clear |

Comparatives can be repeated for greater emphasis, offering exactly the same effect as the use of "even." ("Less and less" follows the same rule.)

qualified |

more qualified |

more and more qualified |

most qualified |

wealthy |

wealthier |

wealthier and wealthier |

wealthiest |

prepared |

less prepared |

more and more prepared |

least prepared |

clear |

less clear |

less and less clear |

least clear |

Edgar Allan Poe's famous poem, "The Raven," ends on the ominous line, "Quoth the raven ever more." Poe meant that the raven would be forever stating Lenore's name, for the rest of its ravenous life, from that moment onward. When there isn't already a precedent for comparison, but you still want to create the sense of ongoing momentum or progress, you may use the adverb "ever." If you have a hard time remembering this rule, just think of something progressing, forever and ever building its momentum. If you use "ever," though, there cannot be a superlative degree, for the process of improvement never ends and cannot have an ultimate form:

competent |

more competent |

ever more competent |

wise |

wiser |

ever wiser |

few |

fewer |

ever fewer |

It's uncommon, but not unheard of, to use "ever less" to indicate a progressive decrease. It just seems like an unnecessary oxymoron. (An oxymoron is two or more words that are arranged paradoxically, as in "His speed is becoming increasingly slower"; increasing speed should be faster, not slower, but the sense of this statement is nonetheless accurate.) The concept "more of what's less" seems contradictory, and, for the most part, the grammarians agree. The preferred method is to find a version of the adjective using prefixes and suffixes to suggest its opposite:

relevant |

less relevant |

ever more irrelevant |

happy |

less happy |

ever more unhappy |

hopeful |

less hopeful |

ever (more) hopeless |

Whenever I think of the strangeness of "ever less," I inevitably think of NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft leaving our solar system and the reach of our son's gravity. Then, we could describe the Voyager I spacecraft using all methods of progressive degree:

Although "ever" prevents you from using a superlative degree, you can still express "ever" in a manner implying the superlative if you use the adverb phrase "more than ever." Typically, adverb phrases like "more so" and "more than ever" are used to modify verb and verb phrases, not one-word adjectives. The exception, however, is the participial phrase: a verbal that acts like an adjective. Here are two examples:

Present Participial Phrase

Past Participial

Unless you're intentionally joking around (e.g., "bestest buddy" "mo' better blues" "hostess with the mostest"), the following will incur the wrath of your English teacher. Be told!

Not... |

But, rather... |

less dryer |

less dry |

least farthest |

least far |

least hardest |

less hard*/least hard |

less angriest |

less angry/least angry |

more kinder |

kinder |

most gorgeousest |

more gorgeous |

more cleverest |

cleverer (or, more clever)/cleverest (or, most clever) |

most sweeter |

sweetest |

Even those adjectives naturally ending in -est or -er when they're in their base form—even these can create the appearance of redundant comparative and superlative forms, which is frowned upon. In such circumstances, you may need to bend the rules a little and choose the comparative and superlative form that is least awkward:

Not... |

But, rather... |

||

honest |

honester |

honestest |

more/most honest |

earnest |

earnester |

earnestest |

more/most earnest |

super |

superer |

superest |

super* |

utter |

utterer |

utterest |

utter* |

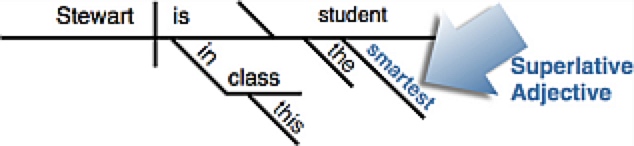

Superlative adjectives are really no different from other adjectives. Superlatives imply that the comparisons are over, and an ultimate choice has revealed itself:

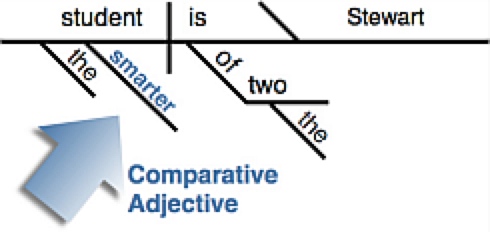

In this example, Steward stands above the others. Whatever comparison or contest was made, it's already in the past—the decision has been made. Therefore, when diagramming a superlative adjective, all we have to worry about is what noun it modifies: Comparative adjectives can modify in the same straightforward way:

If you've looked ahead, then you already know there's something more complex about this topic, just by virtue of how many more words it takes to explain it. One day, you and future generations may forgive us for what we've done to the diagramming of comparative statements. One day. For now, just pick a safe-word and read on.

Even that one punctilious, bee-hived English instructor you once thought was ancient but now realize was just ten years older than you are now—the one you wish you could thank for putting the fear of comma errors into you when you were nine years old—even she (or he—why not?) would groan the groan of the dispossessed if you were to ask how to diagram comparative clauses. It confounds me as to why something so simple to put into words should be so difficult to convey in the logic of a sentence diagram. Perhaps the fault lies within our language, rather than in our stars or any shortcomings of the diagramming process. After all, sentence diagramming isn't just about spreading out and reorganizing the words of a sentence as you would a sock drawer in disarray. A sentence diagram is a linguistic blueprint; it's as elegant, logical, and nuanced as programming code. Perhaps that's why both share the idea of "syntax." If it can't be depicted reasonably in a sentence diagram, perhaps something is actually amiss with the way we express it.

I use the word "amiss" here with some irony, for the issue that most stumbles us when we want to diagram comparative statements is their missing words, which is important to maintaining parallelism. "Missing words?" you say? "Is there a 'Bermuda Triangle' into which words fall and never return?" (Actually, yes. It's called "texting," but that's a topic for another day.) The missing words of comparative statements are about the words on the other side of the parallel mirror: faulty parallelism is the number one mistake writer's commit when expressing comparison; while ordinary clauses and phrases tend to be a straightforward puzzle of reasoning, comparisons are far less linear.

"Parallelism" is not unique to comparative statements. It simply means that the parts of speech and the syntax chosen to express one part of a complex idea are identical to those in another part. If you play cards, then drawing an analogy to suits might help to make sense of this: a straight flush can be recognized in two different suits because each uses the same cards in the same order. In other words, there's a recognizable template to follow that determines whether one straight flush parallels another straight flush. So it goes in grammar. Take any well-known example of hendriatis. ("Hendriatis" is a figure of speech consisting of three words, arranged as a kind of motto or catch phrase.) What makes them memorable is that they follow a pattern: each part of the phrase is identical to the others in some way. When they're not, then the template was not followed and something about the phrase sounds "out of joint":

Parallel |

Not Parallel |

Eat, drink, and be merry. |

Eat, drinks, and merriment. |

Gas, grass, or ass. |

Pay for gas, some grass, or your ass. |

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. |

Living, liberty, and happy. |

Love it, wish it, get it. |

Love it, wishing for it, attainment. |

Reduce, reuse, and recycle. |

Reduce, reusable, and recycling. |

Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll. |

Have sex, taking drugs, and rock 'n' rollers. |

Try, try, and try again. |

Trying, make further attempt, and again. |

Wine, women, and song. |

Wine, womanize, and singing. |

In the second set of examples above, all the hendriatis suffers from lack of parallel structure. Take, for instance, "Reduce, reusable, and recycling." This phrase is not parallel because it has three different parts of speech in succession: a verb, an adjective, and a gerund. We can make them parallel by committing all of them to being the same part of speech:

Parallelism affects larger systems of expression, too, such as a series of independent clauses in a compound sentences, a series of phrases, statements linked by correlative conjunctions, and—to get back to our main point—comparisons.

Ah, comparisons. What does the following sentence mean? What's the actual comparison being made in it?

If you said Sheila's winning a contest with her friends about who can meet more celebrities, you'd be wrong. The literal, linear interpretation of the comparison above means that the number of celebrities Sheila has met is greater than the number of friends she has met, because "us" is an object pronoun, just like "celebrities" is the object of the verb "has met." But, that can't be right! We trust the writer must have meant something else, and, in our heads, subconsciously in the realm where intuitive thinking occurs, we translate the sentence to mean "Our friend, Sheila, has met more celebrities than we." Why is "we" the correct pronoun? Because "Sheila" is a proper noun in the role of the subject of a clause, so the pronoun that occurs after the comparative subordinator "than" must also be a subject pronoun if it is to be parallel to "Sheila." If we really want to clarify the sentence, we'd write, "Our friend, Sheila, has met more celebrities than we have met." Why? Because adding the missing verb "have met" suddenly makes it all clear that "Sheila has met" should be parallel to it. Oh, Sheila!

So, why doesn't he original sentence just do that in the first place?! Where have all the missing words gone that would otherwise round out the comparative statements and remind us of what should be parallel? Well, the annoying fact of the matter is, more often than not, comparative statements are actually shortened versions of full phrases and clauses in whose existence we are expected to put our full faith—full faith in full phrases and clauses that are assumed. See? Comparative statements are just as much metaphysical conceits as they are linguistic ones. And that's why parallellism and comparative adjectives can sometimes be a prickly problem.

Diagramming comparative adjectives, therefore, means taking into account what has not been said as much as what has been said. Let's start with a straightforward sentence with a comparative adjective, "smarter."

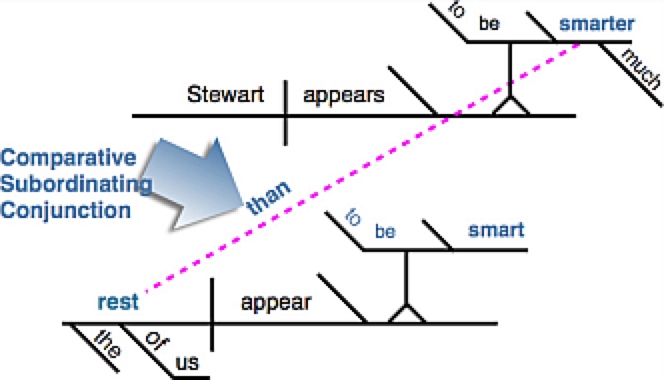

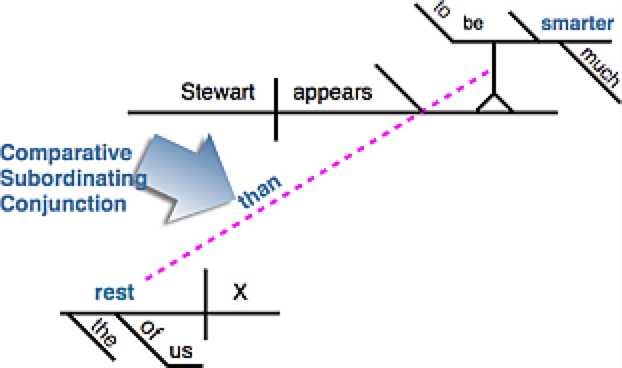

This comparison relies on the subordinating conjunction "than" (called a "comparative subordinator"). Yes, I know: you want "than the rest of us" in this sentence to be a prepositional phrase, but it ain't, because that would ignore the problem of parallel structure: an unseen clause is at work in this sentence, and not only must it be acknowledged, but it must follow a parallel template. When we fill in all the missing words that we believe are there, the full sentence is as follows:

This is how such a sentence would be diagrammed:

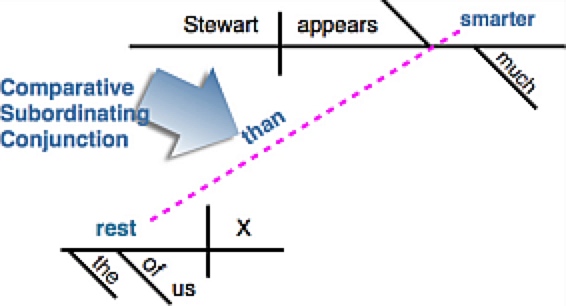

Notice how the subordinating conjunction "than" links to a clause from the comparative adjective "smarter." Your first instinct is to say, "That's unusual." However, subordinate clauses are adverbial, and adverbs can modify adjectives as well as verbs and other adverbs, so, technically speaking, using the comparative subordinator in this manner is consistent with what subordinate conjunctions do. Still, most comparative statements are never this fussy, right? We assume parts of the parallel comparison, so that we don't get lost in all the redundancy and focus on what's most important. To represent that, diagrams put an "X" wherever we make an assumption about parallel parts of speech:

"Appears" is also a linking verb, just like "seems" and "is," so we can streamline the sentence even further by kicking out the redundant infinitive and being as minimalist as we can. Then, the diagram shows just enough to imply what's parallel while overtly showcasing the comparative adjective, "smarter":

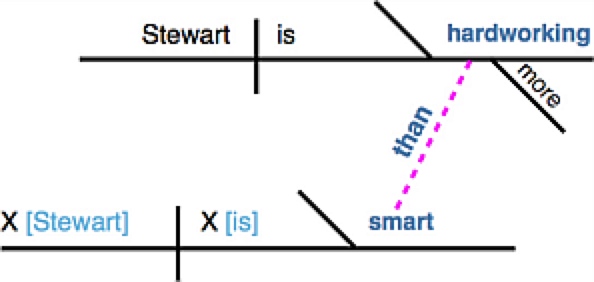

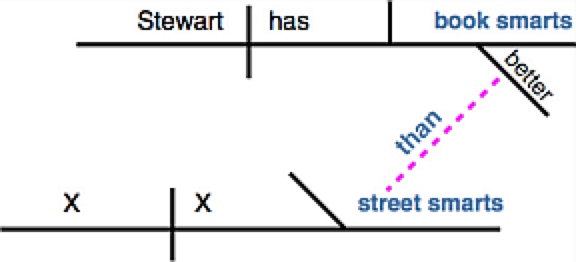

There are different kinds of comparative statements, though. Not every comparison is like the one above. However, when they have the comparative subordinator "than" in common, then they should all show some sort of subordinate clause on their diagram. As long as that dashed line points to the other part of the comparison, and you indicate the phantom words with an "X" in the proper place on the diagram, all should be flush, folded, and fluffy with your universe:

I realize diagramming comparisons can be a pain in the ass. (Forgive me this once for using the pejorative). Comparative adjectives make for an apt example of this. However, if you give yourself up to the higher power of parallel structure and to the blessed assumption that unseen words exist just beyond the veil of syntax, you'll have found just the right opiate to dull the pain.

Karl J Sherlock

Associate Professor, English

Email: karl.sherlock@gcccd.edu

Phone: 619-644-7871